John Patrick is a vocal coach who has worked in film, theatre, and television. He served as the vocal coach for A Number with PlayMakers before working on The Parchman Hour.

The voice carries on it the expression of an experience. Each voice is different just like each person’s perspective is different. The human need for individualized expression is beautifully juxtaposed against the power found in solidarity in The Parchman Hour.

As vocal coach, my job is to support and guide the actors to vocal choices and discoveries that further reveal and communicate the present experiences of the given characters and story, all under the guidance of our esteemed director Mike Wiley. Oh, and to make sure the audience can understand what the actors are saying, lest the artistic choices be for naught.

The unique challenge of working on The Parchman Hour was the sheer amount of characters the audience has to be able to discern from one another. Each with a unique sound and dialect and sometimes one actor may play multiple characters. We live in exciting times with abundant resources for research in this capacity. Audio and video recordings of some of the voices of the actual Freedom Riders exist online. We also have a plethora of recordings of natives from all over the country so we can find dialects that sound indicative of very specific areas of Alabama, Mississippi, and New England where the vast majority of characters hail from. The actors heavily drew on these resources for inspiration in creating living and breathing vehicles for the voices of some historical and fictional characters.

But to simply do an impression of someone historic would not take into account the heart and soul that can only come when an actor identifies personally with the traits and perspective of a character. This marrying of external postures with internal life is a nuanced and exciting journey. We play and make mistakes until a choice is made that resonates deeply with the actor, the ensemble, and ultimately the audience. Then we know we have something powerful to share. Embracing diversity was one of the many tenants of the Civil Rights era so in finding the voice and body of these brave characters we must honor the diverse actors that inhabit them. The actor’s voice must be heard through the dialect and vocal rhythms of the character to celebrate the connection between the two.

The actors do ALL this work. It is my honor to guide and point towards possibilities that the actors already have inside themselves. They may need help shedding light on the sometimes dark and messy catacombs of the creative process, but in the end, the actors make the choice to breathe and dangerously reveal their unique expression of a moment filtered through the perspective of the character they inhabit for a time. How exciting! I am in awe of what actors do and I cannot wait to hear the voices of the Freedom Riders live on in a new generation in The Parchman Hour.

Monday, October 31, 2011

Friday, October 28, 2011

Behind-the-Scenes Video of "The Parchman Hour"

Check out our behind-the-scenes video for The Parchman Hour, featuring playwright-director Mike Wiley with members of the design and production team and the cast!

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

"A Music Director's Perspective"

by Rozlyn Sorrell

Singer/actress Rozlyn Sorrell is a New York native who has performed in music, film, television and theatre in Los Angeles and currently operates Vocal Precision Studio in Raleigh. Rozlyn serves as the music director for The Parchman Hour.

Singer/actress Rozlyn Sorrell is a New York native who has performed in music, film, television and theatre in Los Angeles and currently operates Vocal Precision Studio in Raleigh. Rozlyn serves as the music director for The Parchman Hour. As an educator, I feel this piece is very timely and relevant in the world in which we live today. The economic challenges we face as a nation have affected our educational school system and the way funds are spent. Our world of political correctness jeopardizes historical curriculum and the way texts are written. Their content is watered down and falsified with generalities preventing knowledge in its truest form. As creative arts programs struggle to stay alive, it is so very important that productions such as The Parchman Hour continue to be produced. Future generations will come to know and respect the poignant pen of Mike Wiley, as he is able to communicate the hard realities of a difficult and ugly past in a moving, provocative, honest and entertaining way.

What value, quality and dimension can I add to The Parchman Hour as music director? Ay, there’s the rub. It is my job to support Mike’s vision with musical nuances that accentuate the underlying theme and purpose of the project. It is my job to ensure it is achieved by pulling the qualities he seeks from each artistic cast member. Fortunately, the talented and hard-working cast of this production makes this task less daunting.

The music in this piece helps to soften the heavy blow of harsh dialogue and physical action, but does not eradicate it. It punctuates and emphasizes contradictions of political rhetoric, but does not shove it down your throat. Some music is pounded into the core of your being, while some subtler music just makes you think. You will cry one moment and, before you know it, find yourself clapping your hands, stomping your feet and even singing along. The power of a well-written work is the ability to cause one to experience a roller coaster of emotional confusion. Mike Wiley succeeds – yet again – in accomplishing this feat. It is with great joy that I am able to come along for the ride.

Monday, October 24, 2011

"A Remarkable Journey"

by Kashif Powell

Kashif Powell is a Triangle-based actor, and a Ph.D. student in Performance Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill, making his PlayMakers debut as Stokely Carmichael in The Parchman Hour.

Kashif Powell is a Triangle-based actor, and a Ph.D. student in Performance Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill, making his PlayMakers debut as Stokely Carmichael in The Parchman Hour.It has been such a privilege to work on The Parchman Hour. This project has taken me on a remarkable journey, teaching me profound lessons in courage and sacrifice along the way. One such lesson came this past May when I, along with other members of the cast and the director, Mike Wiley, attended the 50th Anniversary of the Freedom Rides in Jackson, Mississippi.

As waves of Freedom Riders and their families began to flow in, the 15,000-seat auditorium felt like a teapot attempting to contain an ocean. The space ignited with hundreds of stories nearly fifty years old and histories that dated back much further. It still astonishes me that I was able to hear those stories first-hand; I sat next to Jesse Harris who vividly discussed the brutality he experienced while in Parchman and spoke with Joan Trumpauer Mulholland who rode from New Orleans to Jackson with my character, Stokely Carmichael.

The journeys of the Freedom Riders and the legacy of the Freedom Rides filled that space, and in doing so made its way into the hearts and souls of every person present. Now, this production and all those involved are charged with the responsibility of telling the stories of the Freedom Riders and bearing their legacy.

I believe that this play does just that. Like a wave at its summit, it is poised to wash over the audience and pull them right into the thick of the Freedom Rides. So bring your life jackets, because it’s gonna to a fun ride! And when it’s over, hopefully you will leave understanding what I came to understand in May - “freedom does not drop from the sky.” Instead it must be ardently fought for, and, once obtained, lived to its fullest extent. I sincerely thank the many Freedom Riders for not only changing the course of my history, but the path of my future as well. Enjoy the show!

Friday, October 21, 2011

Designing the world of

"The Parchman Hour"

When audiences enter the theater to see The Parchman Hour, their eyes will probably go straight to the life-sized bus onstage.

"The bus became the real tag for me as so much of this story and the story of the civil rights movement involves buses," says set designer McKay Coble, citing the story of Rosa Parks, the strategy of the Freedom Riders and the bus-burning incident at Anniston as examples. But there's more to the set than the bus.

Coble also says she incorporated T.V. sets into the design to highlight the discrepancy between the "lighthearted and a little sexy" vsion of "a bright new world" broadcast on television and the grim problems actually occurring in the '60s.

wikti

"We are using a clip of a Greyhound commercial (and it is one of many travel logs) that show a journey that was supposed to be representative of the trips folks took on buses in 1961," Coble says. "I think the photos of the Greyhounds we see used for the Freedom rides - particularly the one at Anniston - tell a very different story."

As many television sets were still in black and white in 1961, Coble set the majority of the play in the color scheme. "The play starts out in color and we lose it once we get to the prison," she says, citing the achromatic prison uniforms seen in Parchman and the mug shots of the Freedom Riders as examples of the black and white design elements.

Coble says that the return of color at the end reminds audiences "that the movement was forward - still with a way to go, though." The use of color was also inspired by the artwork of Charlotta Janssen, whose work Coble discovering when researching the world of the play.

"She has created remarkable collage and painted portraits based on the mug shots of the Riders that have become so iconographic," Coble says. "It is rich and deep and passionate- makes complete sense to me."

"The bus became the real tag for me as so much of this story and the story of the civil rights movement involves buses," says set designer McKay Coble, citing the story of Rosa Parks, the strategy of the Freedom Riders and the bus-burning incident at Anniston as examples. But there's more to the set than the bus.

|

| The scale model of McKay Coble's set design |

wikti

"We are using a clip of a Greyhound commercial (and it is one of many travel logs) that show a journey that was supposed to be representative of the trips folks took on buses in 1961," Coble says. "I think the photos of the Greyhounds we see used for the Freedom rides - particularly the one at Anniston - tell a very different story."

As many television sets were still in black and white in 1961, Coble set the majority of the play in the color scheme. "The play starts out in color and we lose it once we get to the prison," she says, citing the achromatic prison uniforms seen in Parchman and the mug shots of the Freedom Riders as examples of the black and white design elements.

Coble says that the return of color at the end reminds audiences "that the movement was forward - still with a way to go, though." The use of color was also inspired by the artwork of Charlotta Janssen, whose work Coble discovering when researching the world of the play.

|

| portrait of Rosa Parks by Charlotta Janssen |

"She has created remarkable collage and painted portraits based on the mug shots of the Riders that have become so iconographic," Coble says. "It is rich and deep and passionate- makes complete sense to me."

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Parchman in Context, Part 2

by Ashley Lucas, Dramaturg

Ashley Lucas is production dramaturg for The Parchman Hour by Mike Wiley. The text of this post contains the dramaturgical notes she wrote for the program of the play. This is Part 2 of a two-part essay -- click here to start with Part 1!

The bus rides themselves provided sufficient evidence of the Freedom Riders’ bravery and the depth of their belief in the Civil Rights Movement. However, the Riders further proved their resiliency and their devotion to human rights by maintaining their strength, humor, and commitment to one another during the weeks they spent inside Parchman. Few people have the will to sing about freedom while they are held captive, to engage in hunger strikes when they have already lost much of their physical strength, to hold fast to their ideals when almost no one can see them do it. They faced Parchman and still believed in the dignity of all people. The Parchman Hour does much to capture the sheer force of will of the Freedom Riders, and it raises up their songs and stubborn optimism in the face of terrible violence and irrevocable injustice. They, like Martin Luther King, Jr., Ghandi, and Cesar Chavez, imagined the freedom and equality they did not have and sought to create it with little more than their bodies and voices.

Though the Freedom Riders had a significant hand in the many great triumphs of the Civil Rights Movement, neither they nor the many others who fought for freedom in the 1960s managed to eradicate racism, inequality, or the brutality of incarceration. In 2008 the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) released a report about the “horrific conditions” at Parchman Farm. HIV-positive prisoners began writing to the ACLU in 1998, explaining that:

The ACLU investigation found that of the one hundred twenty men being held in segregation, eighty percent were black and most were convicted of nonviolent offenses. Their report describes these men as being “warehoused in a virtual leper colony and left to die.” ACLU lawyers spent nearly ten years in litigation before they felt that officials at Parchman were finally taking steps to change these conditions in 2007. Life on the Farm doesn’t change much.

The courage of the Freedom Riders—and indeed Mike Wiley’s play—ought to push us out of our seats and into our own forms of protest. We cannot merely marvel at what those in the Civil Rights Movement did for us; we must root out the injustices which surround us today, both those that are readily apparent and those which are deliberately hidden from us. The United States incarcerates 2.3 million people today (one in every one hundred of its citizens) (US Bureau of Justice Website). Our schools are now more segregated than they were in 1954 when the Brown decision was handed down (www.projectcensored.org). In 2010, 17.2 million households in the U.S. did not have enough food to feed their families—a higher rate of hunger than we have seen in this country’s history (www.worldhunger.org). If we admire the Freedom Riders, then we must seek to become them in new ways and in unexpected places. We cannot be content to ignore the persistent legacies of racial inequality, but we must be creative—like the Freedom Riders—and imagine the bus before we can get on it.

Ashley Lucas is production dramaturg for The Parchman Hour by Mike Wiley. The text of this post contains the dramaturgical notes she wrote for the program of the play. This is Part 2 of a two-part essay -- click here to start with Part 1!

---------------------------------

The bus rides themselves provided sufficient evidence of the Freedom Riders’ bravery and the depth of their belief in the Civil Rights Movement. However, the Riders further proved their resiliency and their devotion to human rights by maintaining their strength, humor, and commitment to one another during the weeks they spent inside Parchman. Few people have the will to sing about freedom while they are held captive, to engage in hunger strikes when they have already lost much of their physical strength, to hold fast to their ideals when almost no one can see them do it. They faced Parchman and still believed in the dignity of all people. The Parchman Hour does much to capture the sheer force of will of the Freedom Riders, and it raises up their songs and stubborn optimism in the face of terrible violence and irrevocable injustice. They, like Martin Luther King, Jr., Ghandi, and Cesar Chavez, imagined the freedom and equality they did not have and sought to create it with little more than their bodies and voices.

Though the Freedom Riders had a significant hand in the many great triumphs of the Civil Rights Movement, neither they nor the many others who fought for freedom in the 1960s managed to eradicate racism, inequality, or the brutality of incarceration. In 2008 the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) released a report about the “horrific conditions” at Parchman Farm. HIV-positive prisoners began writing to the ACLU in 1998, explaining that:

they were living in squalor, categorically segregated from the rest of the prison population, and barred from all prison educational and vocational programs and jobs. They told us that they were dying like flies because prison doctors refused to give them the “cocktail” (the triple-drug combination therapy that since 1997 had begun to change HIV from an inevitably fatal disease to a treatable chronic illness). (Winter and Hanlon, “Parchman Farm Blues,” ACLU Website)

The ACLU investigation found that of the one hundred twenty men being held in segregation, eighty percent were black and most were convicted of nonviolent offenses. Their report describes these men as being “warehoused in a virtual leper colony and left to die.” ACLU lawyers spent nearly ten years in litigation before they felt that officials at Parchman were finally taking steps to change these conditions in 2007. Life on the Farm doesn’t change much.

The courage of the Freedom Riders—and indeed Mike Wiley’s play—ought to push us out of our seats and into our own forms of protest. We cannot merely marvel at what those in the Civil Rights Movement did for us; we must root out the injustices which surround us today, both those that are readily apparent and those which are deliberately hidden from us. The United States incarcerates 2.3 million people today (one in every one hundred of its citizens) (US Bureau of Justice Website). Our schools are now more segregated than they were in 1954 when the Brown decision was handed down (www.projectcensored.org). In 2010, 17.2 million households in the U.S. did not have enough food to feed their families—a higher rate of hunger than we have seen in this country’s history (www.worldhunger.org). If we admire the Freedom Riders, then we must seek to become them in new ways and in unexpected places. We cannot be content to ignore the persistent legacies of racial inequality, but we must be creative—like the Freedom Riders—and imagine the bus before we can get on it.

Labels:

Ashley Lucas,

Dramaturg,

Mike Wiley,

The Parchman Hour

Monday, October 17, 2011

So who were the Freedom Riders?

PlayMakers Repertory's upcoming show, The Parchman Hour: Songs and Stories of the '61 Freedom Riders, focuses on the story of a brave and determined group of men and women who had a significant impact on the Civil Rights Movement. Here's some inspirational historical context to get you ready to see the show.

It started with the Nashville Student Group. Upon successfully desegregating lunch counters and movie theaters in their city, the band of college students decided to challenge the Jim Crow laws throughout the South by traveling the country on public buses.

On May 5th, 1961, the group of students, black and white, sat together on their first bus and ignored "white" and "colored" designations at their stops. Though the U.S. Supreme Court had outlawed segregation in public facilities three years earlier, these acts were still considered criminal in the Deep South and the Freedom Riders became the victims of beatings by angry mobs along their route.

On Mother's Day, 1961, a mob in Anniston, Alabama, slashed their bus's tires and threw a firebomb inside. When the Riders tried to escape, they encountered the mob waiting outside the bus weilding lead pipes and baseball bats. Though an undercover agent intervened to precent imminent lynchings, the group was beaten a second time that day when they arrived in Birmingham. Soon afterward members from to CORE (the Committee of Racial Equality), SNCC (the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) and the SCLC (the Southern Christian Leadership Conference)joined the Freedom Rides.

Police soon arrested 350 participants, filling Mississippi jails. Many of the Freedom Riders were transferred to the maximum-security prison at Parchman Farm near Jackson, Mississippi and endured humiliating and torturous conditions.

Upon their release the Riders continued their efforts, inspiring other movements to spring up to challenge segregation laws. Five months after the first ride, the Interstate Commerce Commission enacted a tougher law banning segregation in public facilities.

For more information, check out the Freedom Riders Foundation's website.

It started with the Nashville Student Group. Upon successfully desegregating lunch counters and movie theaters in their city, the band of college students decided to challenge the Jim Crow laws throughout the South by traveling the country on public buses.

|

| A group of Freedom Riders ready to depart. Source: www.forusa.org |

On May 5th, 1961, the group of students, black and white, sat together on their first bus and ignored "white" and "colored" designations at their stops. Though the U.S. Supreme Court had outlawed segregation in public facilities three years earlier, these acts were still considered criminal in the Deep South and the Freedom Riders became the victims of beatings by angry mobs along their route.

On Mother's Day, 1961, a mob in Anniston, Alabama, slashed their bus's tires and threw a firebomb inside. When the Riders tried to escape, they encountered the mob waiting outside the bus weilding lead pipes and baseball bats. Though an undercover agent intervened to precent imminent lynchings, the group was beaten a second time that day when they arrived in Birmingham. Soon afterward members from to CORE (the Committee of Racial Equality), SNCC (the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) and the SCLC (the Southern Christian Leadership Conference)joined the Freedom Rides.

|

| The bombing of a Freedom Riders bus. Source: www.birminghamarchives.org |

Police soon arrested 350 participants, filling Mississippi jails. Many of the Freedom Riders were transferred to the maximum-security prison at Parchman Farm near Jackson, Mississippi and endured humiliating and torturous conditions.

Upon their release the Riders continued their efforts, inspiring other movements to spring up to challenge segregation laws. Five months after the first ride, the Interstate Commerce Commission enacted a tougher law banning segregation in public facilities.

For more information, check out the Freedom Riders Foundation's website.

Friday, October 14, 2011

We Have a Bus!

by Laura Pates, Shop Lead on The Parchman Hour

Laura Pates is a first-year Technical Production MFA student who tracked down and transported a real 1960s bus into the Paul Green Theater to become part of the set for The Parchman Hour.

The bus is one of the main elements of Mckay's set design and references many incidents in the Civil Rights Movement. I was given the task of finding a 1950s-60s era city bus within our available budget and driving distance. I started by contacting every junk yard, scrap yard, wrecking company and bus company within a 2 hours radius of Chapel Hill. Through research and the help of some people I spoke to, I was put into contact with a man in Warsaw, NC who knew everybody and everything there is to know about buses in the country. He gave me the name of a man in Fayetteville who had exactly what we needed (among roughly 90 other buses he has behind his house). I then contacted him and arranged a time for us to drive to Fayetteville, find our bus, and arrange a deal.

Laura Pates is a first-year Technical Production MFA student who tracked down and transported a real 1960s bus into the Paul Green Theater to become part of the set for The Parchman Hour.

|

| Laura Pates and production manager Michael Rolleri pose by the bus (before it was chopped up). |

|

| The interior of the bus |

The next step was the most interesting and definitely the most fun. Our entire crew took 3 trucks with 2 trailers and every tool we could think of to cut a 40' long bus literally in half. We sectioned it into about 7 pieces as we had to carry the pieces through woods and a maze of buses, out to our trucks. We brought the pieces back to the theatre and have begun reassembling the bus in our scene shop. It has been a long process and we ran into many obstacles, but the end product makes it more than worth the effort.

|

| Disassembling the bus |

Come check out the bus in our production of The Parchman Hour, running October 26 - November 13!

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Parchman in Context, Part 1

by Ashley Lucas, Dramaturg

Ashley Lucas is production dramaturg for The Parchman Hour by Mike Wiley. The text of this post contains the dramaturgical notes she wrote for the program of the play. This is Part 1 of a two-part essay -- check back next week for Part 2!

Since its establishment in 1901, the Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm, has had a reputation for being one of the bloodiest and most dangerous prisons in the United States. A former plantation owned by a family named Parchman, the prison’s legacy of farm labor and a mostly black prisoner population remain in place to this day. Historically, most prisoners at Parchman have worked in the fields, tending the cotton by hand for ten hours a day, six days a week. Though prisoners now grow vegetables rather than cotton, they still work the same fields that their enslaved ancestors once plowed. In 2010, the incarcerated workers at Parchman spent 732,326 hours in agricultural labor (Mississippi Department of Corrections Website). Some things don’t change much over time, especially in prison, especially in the South.

Since its establishment in 1901, the Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm, has had a reputation for being one of the bloodiest and most dangerous prisons in the United States. A former plantation owned by a family named Parchman, the prison’s legacy of farm labor and a mostly black prisoner population remain in place to this day. Historically, most prisoners at Parchman have worked in the fields, tending the cotton by hand for ten hours a day, six days a week. Though prisoners now grow vegetables rather than cotton, they still work the same fields that their enslaved ancestors once plowed. In 2010, the incarcerated workers at Parchman spent 732,326 hours in agricultural labor (Mississippi Department of Corrections Website). Some things don’t change much over time, especially in prison, especially in the South.

Parchman’s notoriety as a place of terror long predates the arrival of the Freedom Riders in 1961. After the end of the Civil War, much of the South—and Mississippi in particular—persisted without much infrastructure of any kind. Devastated by the economic and human cost of the war, Mississippians of all racial backgrounds now faced not only the confusion of Reconstruction but also the new legal status of the 400,000 blacks in the state. White legislators quickly drafted the first Jim Crow laws, and Parchman—the only maximum security men’s facility in Mississippi to this day—became the destination for a great many black men (and some women) who were put to work both on the farm and outside of it as part of the convict lease system. Most of the major cities in the South were rebuilt during Reconstruction on the backs of prisoners working on chain gangs (a practice which continues today in Arizona). Both in terms of their monetary worth and their health and safety, blacks had been more valuable as slaves than they were as prisoners. A slave, like any other piece of livestock, needed to be kept in good working condition if a slave owner wanted to maximize his or her productivity. A prisoner, however, ceased to be an asset and could be worked to death without any fiscal loss to the state. The practice of laboring prisoners literally to death was so common that, “Not a single leased convict ever lived long enough to serve a sentence of ten years or more” (Oshinsky, p. 46).

Even those not placed on the chain gangs risked death each day at Parchman. The field laborers at Parchman are still patrolled by guards on horseback carrying rifles. Guards punished prisoners with such severe beatings that many died from the lashes of a leather whip known as Black Annie. Prison administrators and guards also employed the biggest and toughest prisoners to strong arm their peers into submission, even offering guns to some of them to shoot anyone who tried to escape while working in the fields. The severity of the conditions at Parchman prompted a lawsuit in 1972 in which the Honorable William C. Keady declared the prison “an affront ‘to modern standards of decency.’” He ruled for an immediate end to many disciplinary practices at Parchman, including,

Mike Wiley’s new play, The Parchman Hour, gives audiences a glimpse of this prison in 1961 when a group of black and white civil rights activists known as the Freedom Riders served thirty-nine days on the infamous farm after being arrested in Jackson, Mississippi. On May 4, 1961, the first Freedom Ride set out from Washington, DC, carrying thirteen men and women on Trailways and Greyhound buses. These travelers meant to assert the basic right for whites and blacks to sit with one another on a bus, anywhere in the United States. Their peaceable action met with intense hostility from segregationists. By the time the Freedom Riders reached Jackson, Mississippi, they had already faced many beatings and murderous mobs. Under such circumstances, one might be tempted to assume that they were likely to be safer in prison than on these ill-fated buses, but the protestors knew Parchman’s reputation well and had every reason to fear for their lives when they were brought to the legendary farm. Their ride for freedom ended in incarceration.

This is Part 1 of a two-part essay by Ashley Lucas. Check back next week for Part 2!

Ashley Lucas is production dramaturg for The Parchman Hour by Mike Wiley. The text of this post contains the dramaturgical notes she wrote for the program of the play. This is Part 1 of a two-part essay -- check back next week for Part 2!

------------------------------------

Throughout the American South, Parchman Farm is synonymous with punishment and brutality, as well it should be.

-David M. Oshinsky

Since its establishment in 1901, the Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm, has had a reputation for being one of the bloodiest and most dangerous prisons in the United States. A former plantation owned by a family named Parchman, the prison’s legacy of farm labor and a mostly black prisoner population remain in place to this day. Historically, most prisoners at Parchman have worked in the fields, tending the cotton by hand for ten hours a day, six days a week. Though prisoners now grow vegetables rather than cotton, they still work the same fields that their enslaved ancestors once plowed. In 2010, the incarcerated workers at Parchman spent 732,326 hours in agricultural labor (Mississippi Department of Corrections Website). Some things don’t change much over time, especially in prison, especially in the South.

Since its establishment in 1901, the Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm, has had a reputation for being one of the bloodiest and most dangerous prisons in the United States. A former plantation owned by a family named Parchman, the prison’s legacy of farm labor and a mostly black prisoner population remain in place to this day. Historically, most prisoners at Parchman have worked in the fields, tending the cotton by hand for ten hours a day, six days a week. Though prisoners now grow vegetables rather than cotton, they still work the same fields that their enslaved ancestors once plowed. In 2010, the incarcerated workers at Parchman spent 732,326 hours in agricultural labor (Mississippi Department of Corrections Website). Some things don’t change much over time, especially in prison, especially in the South.Parchman’s notoriety as a place of terror long predates the arrival of the Freedom Riders in 1961. After the end of the Civil War, much of the South—and Mississippi in particular—persisted without much infrastructure of any kind. Devastated by the economic and human cost of the war, Mississippians of all racial backgrounds now faced not only the confusion of Reconstruction but also the new legal status of the 400,000 blacks in the state. White legislators quickly drafted the first Jim Crow laws, and Parchman—the only maximum security men’s facility in Mississippi to this day—became the destination for a great many black men (and some women) who were put to work both on the farm and outside of it as part of the convict lease system. Most of the major cities in the South were rebuilt during Reconstruction on the backs of prisoners working on chain gangs (a practice which continues today in Arizona). Both in terms of their monetary worth and their health and safety, blacks had been more valuable as slaves than they were as prisoners. A slave, like any other piece of livestock, needed to be kept in good working condition if a slave owner wanted to maximize his or her productivity. A prisoner, however, ceased to be an asset and could be worked to death without any fiscal loss to the state. The practice of laboring prisoners literally to death was so common that, “Not a single leased convict ever lived long enough to serve a sentence of ten years or more” (Oshinsky, p. 46).

Even those not placed on the chain gangs risked death each day at Parchman. The field laborers at Parchman are still patrolled by guards on horseback carrying rifles. Guards punished prisoners with such severe beatings that many died from the lashes of a leather whip known as Black Annie. Prison administrators and guards also employed the biggest and toughest prisoners to strong arm their peers into submission, even offering guns to some of them to shoot anyone who tried to escape while working in the fields. The severity of the conditions at Parchman prompted a lawsuit in 1972 in which the Honorable William C. Keady declared the prison “an affront ‘to modern standards of decency.’” He ruled for an immediate end to many disciplinary practices at Parchman, including,

beating, shooting, administering milk of magnesia, or stripping inmates of their clothes, turning fans on inmates while they are naked and wet, depriving inmates of mattresses, hygienic materials and/or adequate food, handcuffing or otherwise binding inmates to fences, bars, or other fixtures, using a cattle prod to keep inmates standing or moving, or forcing inmates to stand, sit or lie on crates, stumps or otherwise maintain awkward positions for prolonged periods. (Gates v. Collier)Death and pain—and the fear of those things—remain part of the atmosphere of most prisons, but the vast seclusion of the 18,000 acres of this former plantation, regional efforts to maintain white supremacy after the Civil War, and the inherent racism of the U.S. criminal justice system enabled a culture of perpetual violence to rule Parchman even more strongly than many other prisons in this country.

Mike Wiley’s new play, The Parchman Hour, gives audiences a glimpse of this prison in 1961 when a group of black and white civil rights activists known as the Freedom Riders served thirty-nine days on the infamous farm after being arrested in Jackson, Mississippi. On May 4, 1961, the first Freedom Ride set out from Washington, DC, carrying thirteen men and women on Trailways and Greyhound buses. These travelers meant to assert the basic right for whites and blacks to sit with one another on a bus, anywhere in the United States. Their peaceable action met with intense hostility from segregationists. By the time the Freedom Riders reached Jackson, Mississippi, they had already faced many beatings and murderous mobs. Under such circumstances, one might be tempted to assume that they were likely to be safer in prison than on these ill-fated buses, but the protestors knew Parchman’s reputation well and had every reason to fear for their lives when they were brought to the legendary farm. Their ride for freedom ended in incarceration.

------------------------------------

This is Part 1 of a two-part essay by Ashley Lucas. Check back next week for Part 2!

Labels:

Ashley Lucas,

Dramaturg,

Mike Wiley,

The Parchman Hour

Monday, October 10, 2011

Costuming the Freedom Riders, part 1

by Rachel Pollock, Costume Designer

I'm currently designing costumes for a very exciting project, the professional world premiere of The Parchman Hour, a new play written and directed by Mike Wiley.

The play chronicles the stories and songs of the Freedom Riders, a group composed mostly of college students who, during the summer of 1961, challenged segregation in the southern US by riding Greyhound and Trailways buses into the Deep South and refusing to observe segregated waiting rooms, restrooms, terminal lunch counter seating, and bus seating.

They met with violent resistance--one bus was firebombed and several of the Riders were beaten so badly they had to be hospitalized. They were not deterred, however, and more busloads of them kept coming--eventually over 300 people in all. Ultimately the state of Mississippi began incarcerating them in the notorious Parchman Farm Penitentiary, where they endured cruel abuse but kept their spirits up with songs and a nightly "vaudeville show," in which they would trade off reciting poetry, delivering speeches and sermons, telling jokes, calling out their contributions to everyone down the row on their cellblock.

In our production, there are several performers (one actor and four musicians) who are costumed as long-term Parchman inmates--men who are not part of the Freedom Riders group, but who instead are part of the Parchman gen-pop, hardened criminals and chain-gang workers who toil in Parchman's fields day in and day out. The uniforms worn by those prisoner characters are the subject of this post.

In researching what the uniforms looked like, I was specifically looking for photographs of prisoners making music, since the majority of our performers costumed in this way will be prominently featured onstage providing the music for the show.

I initially found some photos of prison bands, inmates who toured providing music for public events. These images weren't ultimately useful for my research though, beyond novelty. For one thing, all the images i found of prison bands of the era depicted only white prisoners (no surprise, given the segregation and prejudice of the time), and the majority of men serving long sentences in Parchman were black men.

And, our characters haven't been "polished up for the public." They aren't wearing stage-wear uniforms of clean, new fabric. Our guys are inmates playing music for themselves and those with whom they are incarcerated. They need to look like they just came in from the work detail and have sat down to unwind.

These men found time to play music despite incarceration. Our band represents these men.

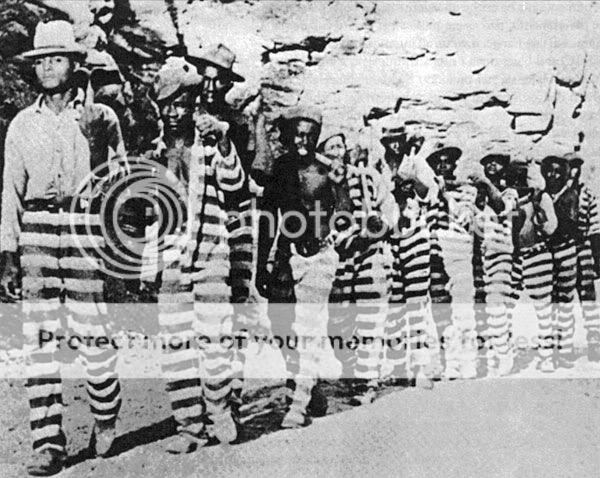

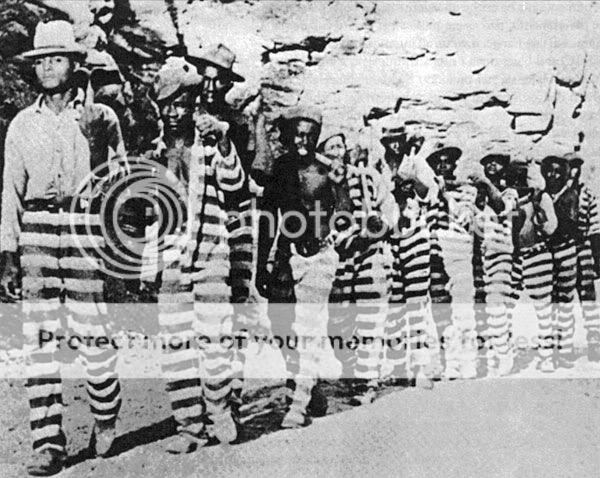

This photo from the early 20th century shows a Parchman work detail returning. Note the variation in sun-fading of the stripes from one man's trousers to another.

This photo depicts Parchman prisoners in 1948 out on detail as music scholar Alan Lomax records their work songs.

Design collage for Pee Wee and the Band. These images became the basis for our conception of what our inmates' uniforms would look like.

I looked into what might be available in terms of pre-made prison-striped garments, but options consist of mostly flimsy cartoonish Halloween costumes, or actual modern-day black-and-white striped prison uniforms, which are now mostly made from ultra-durable polyester fabrics. (Not all modern prisoners have the television-cliche orange jumpsuits.) If you've ever tried to break down or "fade" polyester, you know what an uphill and ultimately losing battle that would mean for the crafts artisan on this show! And, you can't put bright white stripes onstage without adversely affecting the lighting, but you also can't easily tech down a white polyester to a creamier or greyer shade of pale.

I knew that if i wanted to wind up with a group of uniforms that might believably be worn by men serving hard time at Parchman Farm in 1961, we had to explore other options which would afford us more control over our final costumes.

Thankfully, it is entirely feasible in this day and age to simply design your own fabric to whatever specifications you need, and have it digitally printed in your exact yardage requirement. So, this is where the internationally-known, local, print-on-demand fabric production company Spoonflower comes in!

I created a file in Photoshop of a 2" stripe, already aged and faded to a certain degree, and uploaded it to their site. First, we ordered fat quarters in two of their fabrics--cotton twill and linen/cotton canvas--to test the print, the scale of the stripe, and to compare the hand of the fabric. We also did laundry tests on these sample pieces to see how the hand would change as the costumes were worn and laundered.

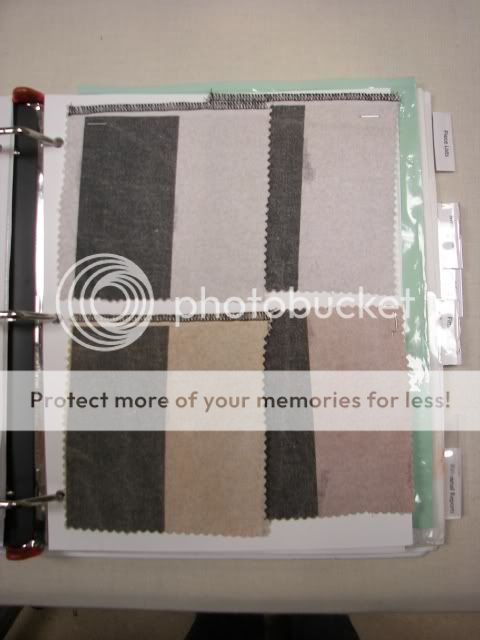

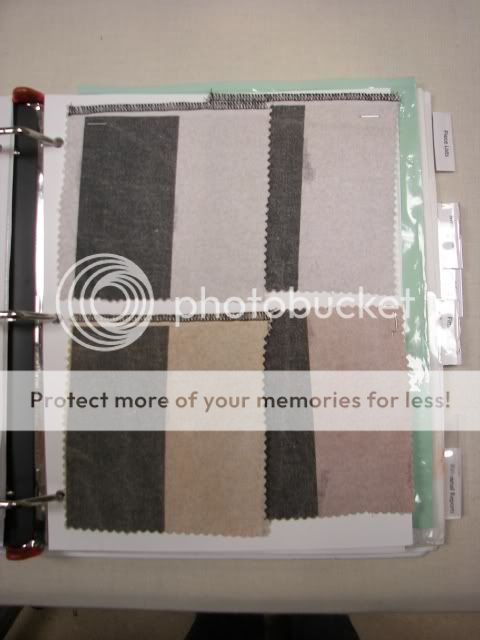

This image shows the cotton twill sample on the left, and the linen/cotton canvas sample on the right. We decided to use the cotton twill, since as the most sturdy weave it would be the most long-wearing for uniforms, and I loved how it reacted to the laundry processing-- slight changes in hand and ink retention.

The samples were washed with soda ash on a high-agitation cycle to help break them in, so they wouldn't look so freshly printed. An unwashed sample is on the right.

We did a set of dye tests at this point, to see what kinds of grime, staining, and yellowing we could incorporate as well. Above are several swatch tests of different washes of dye recipes.

Our shop manager, Adam Dill, contacted the folks at Spoonflower to let them know what we were going to be doing with their fabric and establish a line of communication in case there were any issues or concerns that arose on either end. They were really helpful, and completely on-board about our production timeline and the unusual nature of this project. Then, we ordered 31 yards of the final stripe design in cotton twill.

To give you an idea of the timing and planning of this at this stage of the game, we placed our fabric order two weeks before we wanted to have it in-house. Spoonflower's website lists a turnaround time of 6-7 days from order to shipping, with two more days required for larger quantities like our order. We wanted to make sure there was some wiggle-room. This means that as the designer, Mike and i began talking about these costumes and I started my research literally months ago, back in May and June, and the whole process of ordering the samples and doing the laundry tests happened back in August.

We knew, too, that once the fabric arrived, that there needed to be a week built into the schedule for the stuff to get double-processed (laundry loads, then dye washes). So, the planning for using a digital print has to be really on-point with all areas of production and design--you can't decide to do this on a whim!

Since I am serving as the costume designer on this show, I am not working in my usual capacity as Crafts Artisan. Rather, when i design for the mainstage at Playmakers, it affords one of our graduate students the opportunity to serve as production crafts artisan on a show. That student handles all the responsibilities which would usually be mine--processing dye requests, aging costumes, rubberizing shoes, making or altering or refurbishing hats, etc. I serve in a mentorship capacity, answering questions about specific processes or pointing them toward particular equipment or media or making sure we have extra hands to get the work done if needed, but the day-to-day running of the crafts sub-departmment during Playmakers work hours is left to them. They determine their workflow and ask for undergraduate or overhire help as they see fit, and ensure the crafts get done on time and up to par, as i would. I suppose if we did not have a graduate student who expressed interest in crafts, we might overhire a production crafts artisan, but so far it has been something our grads do pursue with enthusiasm.

The first batch, post-dye-treatment! It looks old and dirty and sweaty, and it's not even a garment yet! Success!

Production Crafts Artisan Adrienne Corral began processing the fabric in batches of six yards each through our 60-gal dye vat. It takes about two hours for her to do one length of the fabric, and is physically demanding work. Imagine suiting up in neoprene scuba gear, rowing a dinghy for fifteen minutes, and then carrying two flour sacks through a sauna. That's kind of what dyeing cotton twill yardage in a 60-gal vat is like, once you've got the neoprene apron and gauntlets and splashproof goggles on, and the bath's up to a boil!

For reference, here's another shot with the original freshly-printed unwashed sample swatch on the right, compared to our ready-to-cut pre-faded gross old prison uniform stripe! Great job, Adrienne!

In the next installment, we'll look at how this fabric yardage turns into costumes, and what else happens to them before they make their appearance onstage in Mike Wiley's incredible new play!

I'm currently designing costumes for a very exciting project, the professional world premiere of The Parchman Hour, a new play written and directed by Mike Wiley.

The play chronicles the stories and songs of the Freedom Riders, a group composed mostly of college students who, during the summer of 1961, challenged segregation in the southern US by riding Greyhound and Trailways buses into the Deep South and refusing to observe segregated waiting rooms, restrooms, terminal lunch counter seating, and bus seating.

They met with violent resistance--one bus was firebombed and several of the Riders were beaten so badly they had to be hospitalized. They were not deterred, however, and more busloads of them kept coming--eventually over 300 people in all. Ultimately the state of Mississippi began incarcerating them in the notorious Parchman Farm Penitentiary, where they endured cruel abuse but kept their spirits up with songs and a nightly "vaudeville show," in which they would trade off reciting poetry, delivering speeches and sermons, telling jokes, calling out their contributions to everyone down the row on their cellblock.

In our production, there are several performers (one actor and four musicians) who are costumed as long-term Parchman inmates--men who are not part of the Freedom Riders group, but who instead are part of the Parchman gen-pop, hardened criminals and chain-gang workers who toil in Parchman's fields day in and day out. The uniforms worn by those prisoner characters are the subject of this post.

In researching what the uniforms looked like, I was specifically looking for photographs of prisoners making music, since the majority of our performers costumed in this way will be prominently featured onstage providing the music for the show.

I initially found some photos of prison bands, inmates who toured providing music for public events. These images weren't ultimately useful for my research though, beyond novelty. For one thing, all the images i found of prison bands of the era depicted only white prisoners (no surprise, given the segregation and prejudice of the time), and the majority of men serving long sentences in Parchman were black men.

And, our characters haven't been "polished up for the public." They aren't wearing stage-wear uniforms of clean, new fabric. Our guys are inmates playing music for themselves and those with whom they are incarcerated. They need to look like they just came in from the work detail and have sat down to unwind.

These men found time to play music despite incarceration. Our band represents these men.

This photo from the early 20th century shows a Parchman work detail returning. Note the variation in sun-fading of the stripes from one man's trousers to another.

This photo depicts Parchman prisoners in 1948 out on detail as music scholar Alan Lomax records their work songs.

Design collage for Pee Wee and the Band. These images became the basis for our conception of what our inmates' uniforms would look like.

I looked into what might be available in terms of pre-made prison-striped garments, but options consist of mostly flimsy cartoonish Halloween costumes, or actual modern-day black-and-white striped prison uniforms, which are now mostly made from ultra-durable polyester fabrics. (Not all modern prisoners have the television-cliche orange jumpsuits.) If you've ever tried to break down or "fade" polyester, you know what an uphill and ultimately losing battle that would mean for the crafts artisan on this show! And, you can't put bright white stripes onstage without adversely affecting the lighting, but you also can't easily tech down a white polyester to a creamier or greyer shade of pale.

I knew that if i wanted to wind up with a group of uniforms that might believably be worn by men serving hard time at Parchman Farm in 1961, we had to explore other options which would afford us more control over our final costumes.

Thankfully, it is entirely feasible in this day and age to simply design your own fabric to whatever specifications you need, and have it digitally printed in your exact yardage requirement. So, this is where the internationally-known, local, print-on-demand fabric production company Spoonflower comes in!

I created a file in Photoshop of a 2" stripe, already aged and faded to a certain degree, and uploaded it to their site. First, we ordered fat quarters in two of their fabrics--cotton twill and linen/cotton canvas--to test the print, the scale of the stripe, and to compare the hand of the fabric. We also did laundry tests on these sample pieces to see how the hand would change as the costumes were worn and laundered.

This image shows the cotton twill sample on the left, and the linen/cotton canvas sample on the right. We decided to use the cotton twill, since as the most sturdy weave it would be the most long-wearing for uniforms, and I loved how it reacted to the laundry processing-- slight changes in hand and ink retention.

The samples were washed with soda ash on a high-agitation cycle to help break them in, so they wouldn't look so freshly printed. An unwashed sample is on the right.

We did a set of dye tests at this point, to see what kinds of grime, staining, and yellowing we could incorporate as well. Above are several swatch tests of different washes of dye recipes.

Our shop manager, Adam Dill, contacted the folks at Spoonflower to let them know what we were going to be doing with their fabric and establish a line of communication in case there were any issues or concerns that arose on either end. They were really helpful, and completely on-board about our production timeline and the unusual nature of this project. Then, we ordered 31 yards of the final stripe design in cotton twill.

To give you an idea of the timing and planning of this at this stage of the game, we placed our fabric order two weeks before we wanted to have it in-house. Spoonflower's website lists a turnaround time of 6-7 days from order to shipping, with two more days required for larger quantities like our order. We wanted to make sure there was some wiggle-room. This means that as the designer, Mike and i began talking about these costumes and I started my research literally months ago, back in May and June, and the whole process of ordering the samples and doing the laundry tests happened back in August.

We knew, too, that once the fabric arrived, that there needed to be a week built into the schedule for the stuff to get double-processed (laundry loads, then dye washes). So, the planning for using a digital print has to be really on-point with all areas of production and design--you can't decide to do this on a whim!

Since I am serving as the costume designer on this show, I am not working in my usual capacity as Crafts Artisan. Rather, when i design for the mainstage at Playmakers, it affords one of our graduate students the opportunity to serve as production crafts artisan on a show. That student handles all the responsibilities which would usually be mine--processing dye requests, aging costumes, rubberizing shoes, making or altering or refurbishing hats, etc. I serve in a mentorship capacity, answering questions about specific processes or pointing them toward particular equipment or media or making sure we have extra hands to get the work done if needed, but the day-to-day running of the crafts sub-departmment during Playmakers work hours is left to them. They determine their workflow and ask for undergraduate or overhire help as they see fit, and ensure the crafts get done on time and up to par, as i would. I suppose if we did not have a graduate student who expressed interest in crafts, we might overhire a production crafts artisan, but so far it has been something our grads do pursue with enthusiasm.

The first batch, post-dye-treatment! It looks old and dirty and sweaty, and it's not even a garment yet! Success!

Production Crafts Artisan Adrienne Corral began processing the fabric in batches of six yards each through our 60-gal dye vat. It takes about two hours for her to do one length of the fabric, and is physically demanding work. Imagine suiting up in neoprene scuba gear, rowing a dinghy for fifteen minutes, and then carrying two flour sacks through a sauna. That's kind of what dyeing cotton twill yardage in a 60-gal vat is like, once you've got the neoprene apron and gauntlets and splashproof goggles on, and the bath's up to a boil!

For reference, here's another shot with the original freshly-printed unwashed sample swatch on the right, compared to our ready-to-cut pre-faded gross old prison uniform stripe! Great job, Adrienne!

In the next installment, we'll look at how this fabric yardage turns into costumes, and what else happens to them before they make their appearance onstage in Mike Wiley's incredible new play!

Labels:

Costumes,

Mike Wiley,

Rachel Pollock,

The Parchman Hour

Thursday, October 6, 2011

"The Parchman Hour":

An introduction by Mike Wiley

by Mike Wiley, playwright and director of The Parchman Hour

"We few, we happy few. We band of brothers. For he who sheds his blood with me today shall be my brother..."

"We few, we happy few. We band of brothers. For he who sheds his blood with me today shall be my brother..."

Words so elequently written by William Shakespeare for the theatre and so bravely echoed by the Freedom Riders for the "beloved community" and "the redeemed America". Men and women, white and black from across America. Students mostly. Heroes, all. In the fall of 2010 at the dawn of the 50th anniversary of those bloody Freedom Rides, students from UNC, Duke, Chapel Hill High School, and NC State once again took up the mantle of those heroic happy few. Tirelessly researching and rehearsing what would become a workshop production and tour of The Parchman Hour. A tour which carried students that had never been out of the Carolinas into the Mississippi Delta, Parchman Prison and beyond.

Young adult actors who were merely seeking the glow of the footlights for themselves became bright channel markers for their generation.

Our time in Mississippi was the culmination of hard work and preparation; yes, but it was more so the culmination of transformation.

A cast of what was once a shy group of babes, who knew very little about the Freedom Rides, arose from wobbly to strong legs with arms outstretched grasping for truths. Truths they'd never been told. Truths they never knew to ask.

Theatre that is vital, that is necessary digs for the truth. Theatre that is healing. Theatre that reconciles. Theatre that is intravenous screams for the truth. And that truth can transform. Transform a person, an audience, as well as communities. The student production had been given a gift. A gift to share their talents, their experience, their knowledge, and most importantly their hope. I saw in my student troupe, everything a director, teacher, or parent could ask for and that was simply and wonderfully a new generation of possibility.

Mike Wiley

"We few, we happy few. We band of brothers. For he who sheds his blood with me today shall be my brother..."

"We few, we happy few. We band of brothers. For he who sheds his blood with me today shall be my brother..."Words so elequently written by William Shakespeare for the theatre and so bravely echoed by the Freedom Riders for the "beloved community" and "the redeemed America". Men and women, white and black from across America. Students mostly. Heroes, all. In the fall of 2010 at the dawn of the 50th anniversary of those bloody Freedom Rides, students from UNC, Duke, Chapel Hill High School, and NC State once again took up the mantle of those heroic happy few. Tirelessly researching and rehearsing what would become a workshop production and tour of The Parchman Hour. A tour which carried students that had never been out of the Carolinas into the Mississippi Delta, Parchman Prison and beyond.

Young adult actors who were merely seeking the glow of the footlights for themselves became bright channel markers for their generation.

Our time in Mississippi was the culmination of hard work and preparation; yes, but it was more so the culmination of transformation.

A cast of what was once a shy group of babes, who knew very little about the Freedom Rides, arose from wobbly to strong legs with arms outstretched grasping for truths. Truths they'd never been told. Truths they never knew to ask.

Theatre that is vital, that is necessary digs for the truth. Theatre that is healing. Theatre that reconciles. Theatre that is intravenous screams for the truth. And that truth can transform. Transform a person, an audience, as well as communities. The student production had been given a gift. A gift to share their talents, their experience, their knowledge, and most importantly their hope. I saw in my student troupe, everything a director, teacher, or parent could ask for and that was simply and wonderfully a new generation of possibility.

Mike Wiley

Monday, October 3, 2011

"PlayMakers as Matchmaker" by Matthew Greer

By Matthew Greer, who plays Dr. Givings in In the Next Room (or the vibrator play)

By Matthew Greer, who plays Dr. Givings in In the Next Room (or the vibrator play)Romance between actors playing opposite one another is nothing new—it’s a cliché without which a myriad of gossip shows and tabloid publications would likely starve. Acting is the only profession I can think of that demands co-workers (who are often complete strangers) to believably create the illusion of intensely intimate relationships. To do so, actors use the script—its language and its imaginary circumstances. But without the commitment of the actors’ other tools - their imaginations, intellects, instincts, emotions, and bodies - no audience member would perceive the characters’ connection as anything but false. Since these tools are the same tools with which all humans relate to one another in the course of “real life,” actors run the risk of having the boundaries between “real” and “imaginary” blur.

I have been a professional actor for over twenty years, and I’ve seen many a “show-mance” ignite during rehearsals. Most cool quickly once the shoot wraps or the show closes, and the “imaginary” forces give way to “real” ones. Sometimes, however, real connections are made, between people, not characters, and these can last a lifetime.

When I first came to work at PlayMakers, fifteen years ago, I was cast as the romantic lead, Posthumus Leonatus, in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. Posthumus is no Romeo. He defies the king and marries the princess, Imogen, just before the play starts. Basically he kisses her, he hits her, and between that, he has no stage time with her - he just rages about her and tries to have her killed. Not really “show-mance” material.

I remember distinctly watching the actress playing Imogen, Christina Rouner, enter the room at Graham Hall (where we rehearsed before the current Center for Dramatic Art was built around the Paul Green Theater) on the first day of rehearsal. A strikingly beautiful six-foot-tall blonde, she easily captured my eye. But what I remember most was the thrill of her reading of the part. She had such facility with the language, talent, technique, humor, and emotional availability. I spent the ten-minute break after the read-through feverishly wondering how I was going to step up and match her performance.

Stage time together or no, we had to believably create a couple who had known each other since childhood, been raised in the same court, and loved each other enough to risk the considerable wrath of the king. We met outside of rehearsal time to imagine their life before the start of the play. As actors also draw heavily on their own life experiences to create aspects of their characters, Christina and I wound up sharing more and more deeply personal stories, and began to discover a great many common interests. On the third day of rehearsal, we began to get the first scene up on its feet, and we had to kiss for the first time. It was, let’s say, much easier than anticipated. We enjoyed more and more time together, and I came to feel I had found a kindred spirit. My parents remind me that I described myself at that time as “completely smitten” by Christina. But would our friendship grow beyond the end of the show, or was it all just another “show-mance?”

I am pleased to report that last Thursday, September 29, marked Christina’s and my tenth wedding anniversary. The fact that we celebrated it during the run of In the Next Room (or the vibrator play) here, at PlayMakers, where it all began, is a storybook touch to a real-life romance.

Matthew lives in New York City with his wife, Christina, an actress, and their two children, Miranda, 8, and Spencer, 5.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)