A few posts ago, I made an update about the show opening tonight for which I have designed costumes, a world premiere of a new script by playwright and director Mike Wiley. The play, The Parchman Hour, takes place partly in Mississippi's notorious Parchman Farm prison.

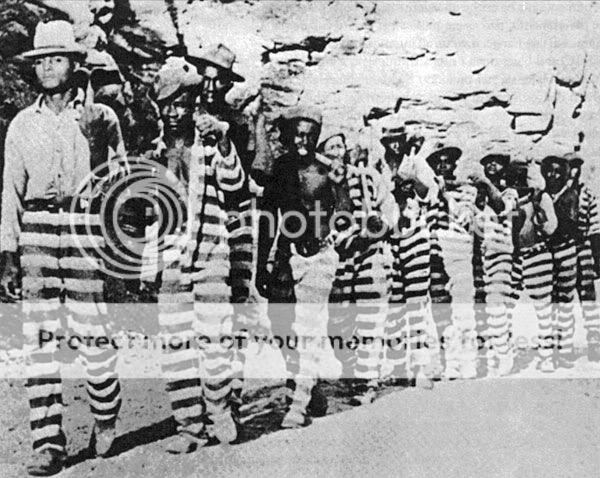

My prior post talked about how I came up with the costume design for the inmate characters doing hard time, whom we know from copious research images wore ragged, faded, black-and-white striped convict uniforms:

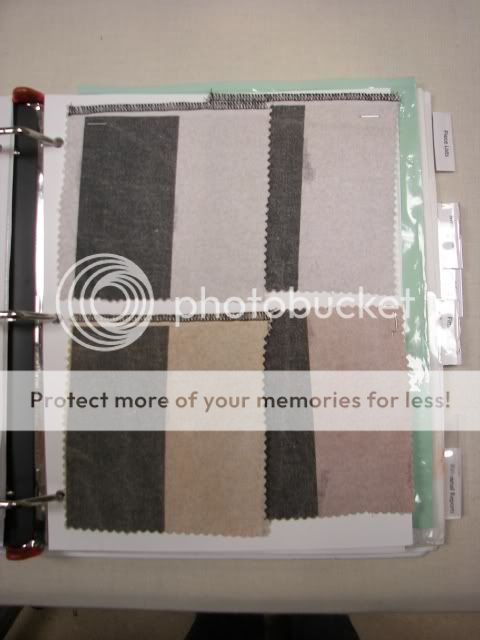

Design collage for the uniforms.

We needed to get fabric to make the uniforms in a very specific stripe dimension and fiber/weave, which we were able to do thanks to the wonderful services of Durham fabric printer Spoonflower. Thanks to modern technology, I can show you some video that the theatre produced as part of the press releases and supplementary media for this show, which is relevant to the project!

Then, lead draper and third-year graduate student Kaitlin Fara drafted patterns for the shirts and trousers, and supervised their construction with the help of two first hands (Claire Fleming and Leah Pelz) and a factory sewing cell of stitchers.

Once the five uniforms were complete, they went back to Adrienne for aging, distressing, and dirtying-up. She used a variety of dye mixtures, textile paints, and screenprinting inks to age the garments, applied with a combination of manual techniques (aka "finger painting"--smearing and scrunching the fabric with colorant smeared onto her gloved hands) and Preval sprayers. After application, she heat-set the effects using both our industrial heat press and a steam chamber, depending on the garment. (Bulky sections with buttons and several thicknesses couldn't go into the heat-press, which is kind of like an enormous straightening iron for hair, so they went into the steamer.)

Adrienne applies some finishing touches of filth to one of the shirts.

Grimed-up trousers on our dyeroom steel table awaiting heat-setting.

Two-minute trailer:

David Aron Damane wears one of the uniforms in the fight at 0:45.

Close-up pan on the band in them at 0:52.

Stage shot of David Aron Damane wearing one of the uniforms.

Also pictured: J. Alphonse Nicholson and the ensemble.

Note how the stage lights minimize all that grime treatment!

There was one other craft project that involved digital design and printing as well, and that was our reproductions of the logo pins that the Freedom Riders from the Coalition of Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee wore on their lapels, to show their solidarity and support, much the same way such logo pins are worn now for political support of fans of a band or whatever. Adrienne took photos of some of the original pins that I provided her as research, and cleaned them up digitally so that they could be uploaded and produced by the company Wacky Buttons, who turned around our small quantity orders (15 of each design) in a matter of a couple days. Here are the masters Adrienne made:

This actually is a great illustration of how digital technologies and online media are changing the way designers can and must think about their shows. The camera operators who shot our trailer video got press shots at such close range that a design element which seems at first thought like an aesthetic conceit (making sure we had the lapel button designs that CORE and SNCC members wore on the rides) becomes differently visually relevant.

Before YouTube trailers for shows, maybe no one but the actors would have gotten a really good look at the pins. Maybe folks on the front row might have barely been able to see the SNCC clasped-hands image. The buttons might just go unnoticed by the majority of the audience so their actual design might not have been very important, but I watched the trailer on full-screen and man, you can really see a couple of them!

The pan shot of the band gets closer to these uniforms than any audience member ever would, so in both of these cases, it was not enough for me to approach the design of this show regarding its appearance at the middle distance, or from the back row, or the front row. There has long been a cliche about costumes and sets, and corners that get cut or illusions that get created: "Will they see it from the front row?" Working for a company that embraces new media, digital technologies, and social platforms for audience engagement is effectively breaking the fourth wall even further down. Something to consider!

Anyhow, that's the dirt (ha!) on the prison uniforms for this world premiere production, opening tonight! It's been an incredible journey. So far, i've sat previews in which people got up and danced, shouted standing ovations, and surviving Freedom Riders got up onstage at the finale. I cannot wait to see what Opening Night holds, and I bet the run is going to bring even more incredible, exciting surprises and energy. I am not exaggerating when I say that this is a game-changing, attitude-changing, life-changing play that will make you want to change your world for the better.

Since its establishment in 1901, the Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm, has had a reputation for being one of the bloodiest and most dangerous prisons in the United States. A former plantation owned by a family named Parchman, the prison’s legacy of farm labor and a mostly black prisoner population remain in place to this day. Historically, most prisoners at Parchman have worked in the fields, tending the cotton by hand for ten hours a day, six days a week. Though prisoners now grow vegetables rather than cotton, they still work the same fields that their enslaved ancestors once plowed. In 2010, the incarcerated workers at Parchman spent 732,326 hours in agricultural labor (Mississippi Department of Corrections Website). Some things don’t change much over time, especially in prison, especially in the South.

Since its establishment in 1901, the Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm, has had a reputation for being one of the bloodiest and most dangerous prisons in the United States. A former plantation owned by a family named Parchman, the prison’s legacy of farm labor and a mostly black prisoner population remain in place to this day. Historically, most prisoners at Parchman have worked in the fields, tending the cotton by hand for ten hours a day, six days a week. Though prisoners now grow vegetables rather than cotton, they still work the same fields that their enslaved ancestors once plowed. In 2010, the incarcerated workers at Parchman spent 732,326 hours in agricultural labor (Mississippi Department of Corrections Website). Some things don’t change much over time, especially in prison, especially in the South.

"We few, we happy few. We band of brothers. For he who sheds his blood with me today shall be my brother..."

"We few, we happy few. We band of brothers. For he who sheds his blood with me today shall be my brother..."